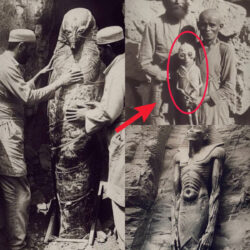

Peruvian elites during the 1100s were not difficult to recognize: they had unusually prolonged skulls.

Significant individuals from the old Collagua bunch in Peru rehearsed head-molding, and an extended, lengthened look turned into a superficial point of interest for first class Collagua.

The Collagua, who lived in the Colca Valley of southeastern Peru, reasonable altered the heads of children utilizing swathes or unique caps, to lengthen their heads and make ‘outsider formed’ skulls.

As per new exploration, these head-molding practices might have given a representative premise to the participation of first class bunches during a time of extreme struggle.

Be that as it may, the class limits framed through head-forming may have added to developing social disparity even before the time of the Incan domain’s extension in South America.

Be that as it may, history specialists are as yet uncertain about what befell the Collagua public and the adjoining Cavanas individuals.

The two gatherings lived during a period of contention, after the breakdown of two unmistakable Andean social orders in 1100, and before the Incan Domain’s development toward the start of the fifteenth hundred years.

Velasco, who has concentrated on Collagua skull shapes crossing a 300-year time span, observed that the stretched skulls were progressively connected with economic wellbeing.

Velasco concentrated on a sum of 211 skulls of embalmed people covered in two Collagua burial grounds, finding proof of the societal position connect.

Significant individuals from the old Collagua bunch in Peru rehearsed head-molding, and an extended, stretched look turned into a superficial point of interest for tip top Collagua. Bandages or special hats were probably used by the Collagua to change the shape of babies’ heads.

For instance, substance investigations of bones observed that ladies with lengthened heads are many food sources.

Likewise, Collagua ladies with extended skulls were found to have experienced undeniably less skull harm actual assaults than ladies who didn’t have comparably altered skulls.

Until know, the greater part of the information about this training came from composed accounts from Spanish conquerors during the 1500s.

According to these documents, some Collagua people had tall, thin skulls, whereas Cavana people had wide, long skulls and may have made them with wooden planks.

Presently, Velasco’s review has broadened our insight on the subtleties of these practices.

The skulls and bones were found in entombment structures worked against a precipice faces, which were probable just for high-status individuals.

Conversely, entombment regions in caves and under neighboring rough shades were for everyday citizens.

Velasco was able to classify some of the samples’ skulls into early or late pre-Inca groups through radiocarbon analyses.

A sum of 97 skulls (counting 76 from ordinary citizen entombment regions) had a place with the early gathering (1150-1300), and 38 of these (39%) had been changed.

Some were extended, though others were altered into wide shapes.

14 of these skulls were stretched, and of these 14, 13 came from low-positioning individuals, recommending that everyday citizens initially began adjusting their skulls to lengthen them.

Be that as it may, on the grounds that main 21 skulls having a place with first class individuals were found in the early gathering, it might prompt an underrate of the early recurrence of extended heads among tip top individuals.

Paradoxically, among 114 skulls from first class entombment regions in the late period (1300-1450) – 84 (74 percent) had changed shapes, most of which where extremely lengthened.

No proof was found to decide whether everyday citizens likewise had extended skulls in the late period.