The opportunity revelation underneath an almost 2,000-year-old pyramid prompts the core of a lost human progress

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ba/4d/ba4d1156-8c5c-4bab-8a01-63e8e4ed5a9b/jun2016_c03_teotihuacan.jpg)

Teotihuacán, a pyramid-studded pre-Aztec metropolis 30 miles northeast of present-day Mexico City, was battered by a torrent of rain in the fall of 2003. Water covered the dig sites; At the main entrance, rows of souvenir stands were swept away by a torrent of mud and debris. The central courtyard’s grounds buckled and broke. Sergio Gómez, an archaeologist with Mexico’s National Institute of Anthropology and History, arrived at work one morning to find a nearly three-foot-wide sinkhole at the base of the Temple of the Plumed Serpent, a large pyramid in the southeast quadrant of Teotihuacán.

“My first thought was, ‘What am I looking at exactly?'” Gómez recently informed me. “How exactly are we going to fix this?” was the second question.

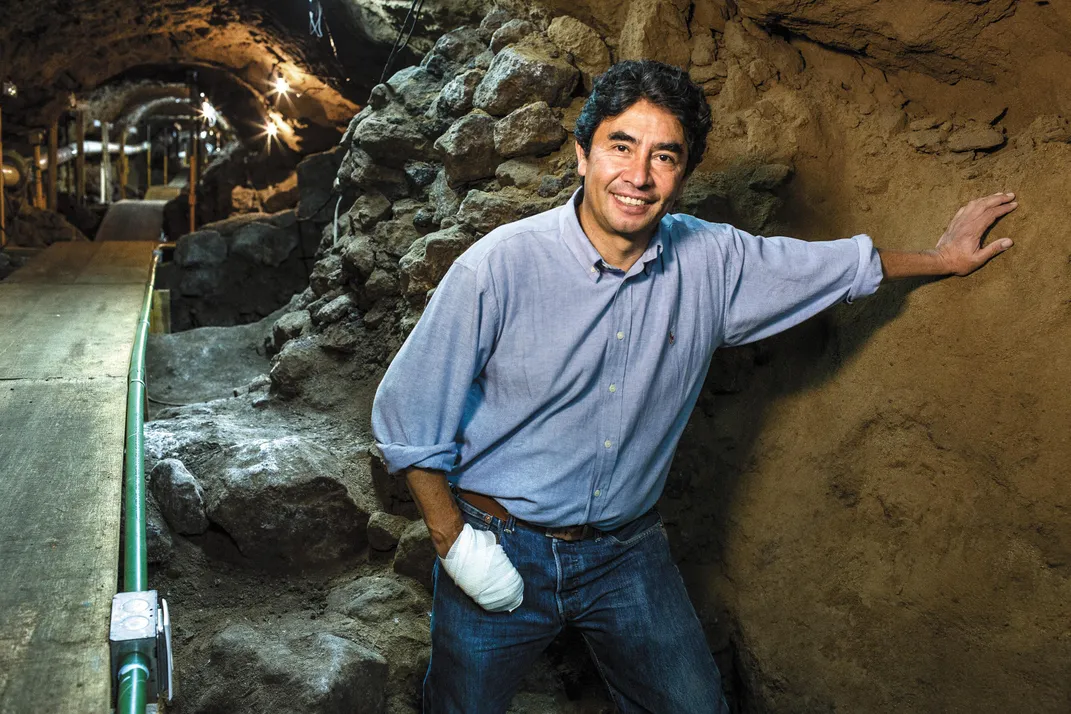

Gómez is wiry and little, with articulated cheekbones, nicotine-stained fingers and a head protector of thick dark hair that adds several creeps to his level. He has worked in and around Teotihuacán, which was once a cosmopolitan center of the Mesoamerican world, for the past three decades—almost all of his professional career. He frequently remarks that very few living people know the area as well as he does.

Furthermore, taking everything into account, there wasn’t a thing underneath the Sanctuary of the Plumed Snake past soil, fossils and rock. Gómez got a spotlight from his truck and pointed it into the sinkhole. Nothing: only shadows. So he tied a line of weighty rope around his midriff and, with a few partners clutching the opposite end, he slipped into the murk.

In the middle of what appeared to be a man-made tunnel, Gómez died. He explained to me, “The tunnel itself was blocked in both directions by these immense stones, but I could make out some of the ceiling.”

The major monuments of Teotihuacán (pronounced tay-oh-tee-wah-KAHN) were arranged on a north-south axis by the city’s architects. The so-called “Avenue of the Dead” connected the largest structure, the Temple of the Sun, to the Ciudadela, the southeasterly courtyard that was home to the Temple of the Plumed Serpent. Gómez was aware that a short tunnel beneath the Temple of the Sun had previously been discovered by archaeologists. Under the Temple of the Plumed Serpent, he thought he was looking at a mirror tunnel that led to a subterranean chamber. If he was right, it would be a remarkable discovery—the kind of accomplishment that can launch a career.

He explained to me, “The issue was that you can’t just dive in and start tearing up the earth.” A clear hypothesis is necessary, and approval is required.

Gómez began devising his strategies. In order to shield the sinkhole from the prying eyes of the hundreds of thousands of tourists who visit Teotihuacán each year, he set up a tent over it and coordinated the delivery of a high-resolution ground-penetrating radar device the size of a lawnmower with assistance from the National Institute of Anthropology and History. Starting in the early long stretches of 2004, he and a handpicked group of nearly 20 archeologists and laborers examined the earth under the Ciudadela, returning each evening to transfer the outcomes to Gómez’s PCs. The digital map was finished by 2005.

From the Ciudadela to the center of the Temple of the Plumed Serpent, the tunnel was approximately 330 feet long, as Gómez had suspected. The opening that had showed up during the 2003 tempests was not the genuine entry; that was a few yards back, and large boulders appeared to have been used to seal it off nearly 2,000 years ago. Gómez thought to himself that whatever was in that tunnel was meant to remain hidden forever.

Teotihuacán has long been regarded as one of Mesoamerica’s greatest mysteries: the site of a goliath and persuasive culture about which frustratingly little is perceived, from the states of its ascent to the conditions of its breakdown to its genuine name. In Nahuatl, the Aztec language, Teotihuacán means “the place where men become gods.” The Aztecs probably found the city’s ruins in the 1300s, centuries after it was abandoned, and concluded that a powerful ur-culture—an ancestor of theirs—must have once lived in its vast temples.

The city is situated in a basin at the Mexican Plateau’s southernmost tip, an undulating landmass that serves as Mexico’s core today. The climate is pleasant inside the basin, and the land is dotted with streams and rivers, making it ideal for farming and livestock raising.

Teotihuacán itself was reasonable settled as soon as 400 B.C., however it was exclusively around A.D. 100, a time of strong populace development and expanded urbanization in Mesoamerica, that the city as far as we might be concerned, with its wide roads and stupendous pyramids, was fabricated. Its founders, according to some historians, were refugees who were driven north by a volcano’s eruption. Others have conjectured that they were Totonacs, a clan from the east.

Regardless, the Teotihuacanos, as they are presently known, did right by be talented metropolitan organizers. To reroute the San Juan River under the Avenue of the Dead, they constructed stone-sided canals and began building the pyramids that would form the city’s core: the Temple of the Plumed Serpent, the even larger Temple of the Moon, which is 147 feet tall, and the bulky, sky-obscuring Temple of the Sun, which is 213 feet tall.

Professor emeritus of archaeology and art history Clemency Coggins of Boston University has proposed that the city was planned as a physical manifestation of the creation myth of its founders. Coggins has written that Teotihuacán was laid out in a measured rectangular grid and that the pattern was oriented to the movement of the sun,

Recent evidence suggests that the Mayan religion practiced in the cities of Tikal and El Mirador, hundreds of miles to the southeast, was similar to that of these pyramids: the loving of the sun and moon and stars; the worship of a plumed serpent resembling a Quetzalcoatl; the frequent appearance of a jaguar that serves as both a deity and a guardian of men in art and sculpture.

However quiet custom was evidently not generally enough to support the Teotihuacanos’ association with their divine beings. Saburo Sugiyama, an anthropologist from Arizona State University who had been studying Teotihuacán for decades, and Rubén Cabrera, an anthropologist from Mexico’s National Institute of Anthropology and History, discovered a vault beneath the Temple of the Moon in 2004. Inside the vault were the skeletons of 12 human beings, ten of whom had lost their heads. It is difficult to accept that the custom comprised of clean representative exhibitions,” Sugiyama said at that point. ” It is highly likely that the ceremony created a horrible scene of animal and human sacrifice.

Teotihuacán experienced rapid expansion between 150 and 300 A.D. Local people gathered beans, avocados, peppers and squash on fields brought up in the center of shallow lakes and swampland — a procedure known as chinampa — and kept chickens and turkeys. Teotihuacán was connected to obsidian quarries in Pachuca and cacao groves near the Gulf of Mexico by a number of heavily used trade routes. Cotton rolled in from the Pacific Coast, earthenware production from Veracruz.

Teotihuacán had become the region’s most powerful and influential city by 400 A.D. Private areas jumped up in concentric circles around the downtown area, in the long run containing large number of individual family abodes, not at all like single-story condos, that together may have housed 200,000 individuals.

which was born there. She is not the only historian who sees the city as a metaphor for a larger scale. Michael Coe, a paleontologist at Yale, contended during the 1980s that singular designs may be portrayals of the rise of humanity out of a tremendous and turbulent ocean. ( According to Mesoamericans of the time, the world was thought to have been created from aqueous darkness, as in Genesis.) Consider the Sanctuary of the Plumed Snake, Coe recommended — the very sanctuary that concealed Sergio Gómez’s passage. Coggins referred to the facade of the building as “marine motifs”: waves and what look like shells. The temple, according to Coe, is a symbol of the “initial creation of the universe from a watery void.”

Ongoing hands on work by researchers like David Carballo, of Boston College, has uncovered the sheer variety of the populace of Teotihuacán: Residents of Teotihuacán came from as far away as Chiapas and the Yucatán, according to artifacts and paintings found inside surviving buildings. There were probably Mayan and Zapotec communities there. Teotihuacán was probably one of the first significant melting pots in the Western Hemisphere, as the scholar Miguel Angel Torres, a representative at Mexico’s National Institute for Anthropology and History, recently informed me. Torres asserts, “I think the city grew a little like Manhattan today.” You stroll around through these various areas: Koreatown, Chinatown, and Spanish Harlem. However, the city functions harmoniously as a whole.

The peace did not last long. There is a clue, in the destruction of a portion of the figures that enhance the sanctuaries and landmarks, of occasional shift in power the decision class of Teotihuacán; also, in the portrayal of safeguard and lance carrying heroes, of conflicts with other nearby city-states. Maybe, as a few archeologists proposed to me, nationwide conflict moved throughout Teotihuacán, coming full circle in a fire that appears to have harmed immense segments of the inside of the city around A.D. 550. A visiting army may have started the fire. It’s possible that a massive migration took place.

The city of Teotihuacán was abandoned in 750 A.D., nearly 700 years after it was founded. Its monuments were still filled with treasures, artifacts, and bones, and the buildings were left to be eaten by the brush. If they weren’t killed, the people who used to live in Teotihuacán were probably absorbed into the cultures that lived nearby or traveled the established trade routes to the places in Mesoamerica where their ancestors still lived.

They left behind their secrets. Even after excavations at the site for more than a century, we still don’t know a lot about the Teotihuacanos. They had a semi hieroglyphic composed language of some sort, however we haven’t broken it; We have no idea what the natives called the city or what language it was spoken in. We have some idea of the religion they followed, but we don’t know much about the priestly class, how pious the city’s residents were, or how the courts and military were made. We don’t know exactly what caused the city to be founded, who ruled it for half a millennium, or how it came to be destroyed. “This city wasn’t designed to answer our questions,” said Matthew Robb, the de Young Museum’s Mesoamerican art curator.

Sergio Gómez’s discovery was hailed as a significant turning point in Teotihuacán studies by archaeologists and anthropologists alike, not to mention the mainstream media. The passage under the Sanctuary of the Sun had been to a great extent exhausted by thieves before archeologists could get to it during the 1990s. However, Gómez’s tunnel had been closed off for approximately 1,800 years: Its heirlooms would be spotless.

In 2009, the government gave Gómez permission to dig. He started digging at the tunnel’s entrance, where he built a staircase and ladders that would make getting to the underground site easy. He moved slowly and carefully: every month, a few inches at a time, a few feet. Unearthing was done physically, with spades. The tunnel was cleared of nearly 1,000 tons of earth; after each new section was cleared, Gómez got a three dimensional scanner to report his advancement.

The sum was enormous. Pottery, cat bones, and seashells were present. Human skin fragments were present. Necklaces were elaborate. Rings, wood, and figurines were present. As if in an offering, everything was deposited with care and emphasis. For Gómez, the picture was becoming clearer: Ordinary citizens were not permitted to enter this area.

Tlaloque and Tláloc II, jokingly named after Aztec rain deities whose images appear in early iterations throughout Teotihuacán, were donated by a university in Mexico City to inspect the tunnel’s deeper levels, including the final section, which descended on a ramp an additional ten feet into the ground. The robots, glowing from their cameras like mechanical moles, chewed through the soil and returned with impressive footage on hard drives: The tunnel appeared to come to an open, cross-shaped room filled with more statues and jewelry.

Gómez hoped that this would be the location of his most significant find to date.

I met Gómez before the end of last year, on a burning hot evening. He was having coffee in a foam cup while he was smoking a cigarette. I heard bits of Italian, Russian, and French as the tourists’ tides swept across the grass of the Ciudadela. As if they were tigers in a zoo, a couple from Asia stopped to look at Gómez and his team. With the cigarette dangling from his bottom lip, Gómez gave a stony look back.

I was told by Gómez about the work his team was doing to study the roughly 75,000 artifacts they had found so far. Each one needed to be carefully cataloged, analyzed, and, if possible, restored. I would appraise that we’re around 10% through the cycle,” he said.

The restoration work is being done in a group of buildings close to the Ciudadela. In one room, a young fellow was drawing curios and taking note of where in the passage the items had been found. Nearby, a small bunch of conservators found a seat at a meal style table, twisted around a variety of earthenware. Acetone and alcohol, a mixture used to remove contaminants from the artifacts, gave off a strong odor in the air.

Vania Garca, a technician from Mexico City, informed me, “It might take you months just to finish a single large piece.” She was utilizing a needle prepared with CH3)2CO to clean an especially small break. ” However, some of the other items are exceptionally preserved: They were carefully buried. She recalled having recently discovered a powdery yellow substance at the jar’s bottom. It turned out to be 1,800-year-old corn.

We entered the storeroom after passing through a laboratory where chemical baths were carefully treating tunnel-recovered wood. Gómez stated, “This is where we keep the fully restored artifacts.” A collection of flawless obsidian knives and a statue of a coiled jaguar ready to strike. The materials for the weapons probably came from the Pachuca region of Mexico and were carved by master craftsmen in Teotihuacán. I was offered a knife by Gómez; It was amazingly light. What a general public, no?” He cried out, That has the potential to produce something as powerful and beautiful as that.

Gómez’s team had installed a wobbly ladder attached to the top platform with frayed twine in the canvas tent that was built over the tunnel’s entrance. I plunged cautiously, foot over foot, the edge of my hard cap slipping over my eyes. It was cold and damp, like a grave in the tunnel. To go anyplace, you needed to stroll on your hindquarters, going to the side when the section limited. Gómez’s workers had installed several dozen feet of scaffolding to prevent cave-ins because the ground here is unstable and earthquakes are common. There had been two partial collapses thus far; nobody had been harmed. All things considered, it was hard not to feel a shudder of taphophobia.

Those who contend that the city was ruled by a council of elite families or otherwise bound groups, vying over time for relative influence as a result of the cosmopolitan nature of the city itself, are divided along a division that resembles a fault line in the middle of Teotihuacán studies. The first group, which includes experts like Saburo Sugiyama, has precedent on its side. The Maya, for example, are known for having kings who were aggressive. However, Teotihuacán has offered no such decorations or tombs, unlike Mayan cities, where rulers were buried in opulent tombs and had their faces plastered on buildings.

At first, a lot of the talk about the tunnel under the Temple of the Plumed Serpent was about the possibility that Gómez and his team might finally find one of these tombs and solve one of the most fundamental and enduring mysteries of the city. The concept has been discussed by Gómez himself. In any case, as we climbed through the passage, he spread out a speculation that appeared to stem all the more straightforwardly from the fanciful readings of the city spread out by researchers like Forgiveness Coggins and Michael Coe.

After traveling fifty feet, we came to a wall-carved small inlet. Gómez and his colleagues had discovered the mineral pyrite, which had been hand-enhanced into the rock, as well as mercury traces in the tunnel, which Gómez believed represented water. Gómez explained that the pyrite shards give off a metallic throb in semi-darkness. He unscrewed the nearest light bulb to demonstrate. The pyrite showed signs of life, similar to a far off system. In that instant, it was possible to imagine how the architects of the tunnel might have felt more than a thousand years ago: They had recreated the sensation of standing among the stars 40 feet below ground.

The tunnel beneath the temple dedicated to an all-encompassing aqueous past may represent a world outside of time, an underworld, or a world before, not the world of the living but of the dead, if, as Gómez suggested, the city’s layout was meant to represent the universe and its creation. The eternal day and the Temple of the Sun could be seen high above. The deepest night and the stars below, which are not of this earth.

Gómez led me down a short ramp into the chamber in the shape of a cross directly beneath the Temple of the Plumed Serpent’s heart. With brushes and thin-bladed trowels in their hands, four archaeologists were kneeling in the dirt. Lady Gaga was played from a nearby boombox.

Gómez let me know he had not been arranged for the sheer variety of the items he experienced in the farthermost scopes of the passage: necklaces with the cord still attached. wings in boxes of beetles. Jaguar skeletons Amber balls. Furthermore, maybe most intriguingly, a couple of finely cut dark stone sculptures, each confronting the wall inverse to the entrance of the chamber.

Coggins speculated in a piece he wrote in the latter part of the 1990s that religious practice at Teotihuacán would have been “perpetuated in the linked repetition of ritual,” most likely by a priesthood. Coggins went on to say that this ritual “would have concerned the Creation, Teotihuacán’s role in it, and probably also the birth/emergence of the Teotihuacán people from a cave,” which was a deep, gloomy hole in the earth.

Gómez signaled at the region where the twin figures once stood. ” He explained, “You can imagine a scenario where priests come down here to pay tribute to them”—to the same Creators of the city and the universe.

Gómez has another critical errand to embrace: the excavation of three distinct buried sub-chambers beneath the figurines’ final resting place, the remaining unexplored sections of the tunnel complex. A few researchers hypothesize that the intricate ceremonial contributions in plain view here, and the presence of pyrite and mercury, which held known relationship with the extraordinary among old Mesoamericans, give additional proof that the covered sub-chambers address the doorway to a specific kind of hidden world: the place where the city’s ruler left the living world. Others argue that the mystery of Teotihuacán’s rulers would not be solved by the discovery of long-coveted human remains buried in spectacular fashion: It’s possible that the ruler or holy person who is buried here is just one of many.

For Gómez, the sub-chambers, whether they are loaded up with additional ceremonial relics, or remains, or something totally startling, may be best perceived as an emblematic “burial place”: a place of gods and men, the city’s founders’ final resting place.

I met up with Gómez a few months after I left Mexico. He was just a little bit closer to finding the chambers beneath the tunnel’s end. To avoid causing damage to the ground below, his archaeologists literally used toothbrushes a lot.

He promised me that once his excavation was finished, he would be satisfied, regardless of what he discovered at the tunnel’s end. The quantity of artifacts we’ve discovered,” he paused. You could evaluate the contents for the rest of your life.