From the cliffside way that leads down to the ocean, around four kilometers away, I stop. This is the spot: a cavern, its entry scarcely noticeable. I gaze toward the approaching substance of the stone. I sense it gazing back at me, coaxing with its reserve: many caverns, worked over the course of the hundreds of years from the magma streams of Mount Teide.

Any of them could be the cavern we’re searching for — here, history has not yet been composed. Inside this crevasse in southern Tenerife, the biggest of Spain’s Canary Islands, a dazzling cavern was seen as in 1764 by Spanish official and infantry chief Luis Román. A contemporary neighborhood cleric and essayist depicted the track down in a book on the historical backdrop of the islands: “A magnificent pantheon has quite recently been found,” José Viera y Clavijo composed. “So loaded with mummies that something like 1,000 were counted.” And subsequently the story of the thousand mummies was conceived. (Find out about the various kinds of mummies saw as around the world.) Not many things are more invigorating than exploring the uncertain edge among history and legend. Presently, over two centuries after the fact, in the canyon known as Barranco de Herques — likewise called “gorge of the dead” for its funerary caverns — we wind up in the spot that most nearby archeologists view as the legendary “cavern of the thousand mummies.” There are currently composed facilitates; its area has been passed on by listening in on others’ conversations among a picked not many. The climbers who adventure along the way are abivious to its presence

In the organization of islander companions, I feel advantaged to be shown where they accept their precursors once refreshed. I hunch toward the restricted opening, turn on my headlamp and drop to the ground. To find this secret domain, we creep in on our stomachs for a couple of claustrophobic meters. Yet, there’s a compensation for exposing ourselves to the difficult situation: a tall, extensive chamber unexpectedly opens before me, holding the commitment of an excursion to the island’s past. “As archeologists we expect that the articulation ‘thousand mummies’ was likely a distortion, a method for proposing that there were for sure a ton, a ton — hundreds,” says Mila Álvarez Sosa, a nearby history specialist and Egyptologist.

In the dimness, our eyes gradually change. We review the space for the indications of a necropolis in the wandering magma tube, part of a broad framework across the island. These weren’t the principal mummies to be uncovered on the island. Be that as it may, as per neighborhood legend, an enormous sepulchral cavern like this one held the pantheon of the nine Mencey lords who controlled the islands in precolonial times. The cavern’s area was a carefully monitored secret.

Also, there was no record of it, which simply raised it as the sacred goal of Canarian antiquarianism. Local people keep up with they don’t unveil the area to safeguard the memory of their predecessors who rested there, the Guanches, the Native nation of this island — no particular Guanche populace remains today. Others say it was lost to an avalanche, covered for eternity. (Go past the sea shores in the Canary Islands.)What might have been a conviction for those eighteenth century wayfarers morphedin to legend when the mummies were culled from their resting place and their area was lost. Yet, the not very many — from that cavern and others — that stay in one piece and are held in historical center assortments are assisting researchers with unwinding the anecdote about the archipelago: when and where the primary occupants came from, and how they respected their dead.

Safeguarding the departed forever, Tenerife turned into the last island in the archipelago to fall under the Castilian crown, starting in 1494. It wasn’t the primary experience the islanders had with Europeans, however it would be the last. Álvarez Sosa paints a distinctive difference when, toward the finish of the fifteenth 100 years during the beginning of the Renaissance, warriors showed up on ships with swords and ponies, confronting a group simply rising up out of the Neolithic time, cave tenants clad in creature skins and utilizing simple devices. However, they held a profound regard for their withdrew, fastidiously setting them up for their last process, protecting them.

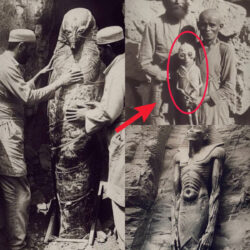

The homesteaders’ interest with death drove them to report the funerary customs carefully. “That predominantly caught the consideration of the Castilian champions,” says Álvarez Sosa. They were especially captivated by the treating system — known as “mirlado” — that prepared the xaxos (Guanche mummies) for an everlasting presence.

In the faintly lit cave, one can’t resist the urge to envision the stunningness that probably grasped Luis Román, permeated with the soul of the Illumination, as he wandered into the necropolis with neighborhood guides determined to gather examples for study. He moved these bodies to Europe, where, by the eighteenth hundred years, mummies became both a logical interest and a curiosity, catching the interest of researchers and gatherers.

The second when Román raised his light, divulging many bodies suspended in time, probably been a combination of blasphemy and thrill. Strangely, the essayist who summed up their visit precluded the cavern’s area, however tragically, this work to shield the cavern from loot eventually fizzled, as various sources affirmed by 1833 that no bodies remained.

As I stand up, shaking the white residue from my hands and knees, my headlamp faintly enlightens the cavern walls. While I realize the chances are thin, a piece of me actually desires to find a xaxo (articulated “haho”) concealed in some secret corner, similarly as Viera y Clavo once portrayed.

The most common way of saving these bodies against the persevering powers of time and nature was shockingly clear. “It’s a similar cycle you would use with food,” makes sense of Álvarez Sosa. “The bodies were treated with dry spices and grease, left to dry in the sun, and smoked over a fire.” This cycle required just 15 days to set up a xaxo, as a conspicuous difference to the 70 days expected for an Egyptian mummy (40 days to get dried out in normally happening natron salt, trailed by 30 days of preserving in oils and flavors prior to filling the hole with straw or fabric and enclosing by cloth). Another striking distinction was the destiny of the xaxos, as Álvarez Sosa recommends, “Some might have wound up at the lower part of the ocean, tossed over the edge during the excursion to the Mainland when warm circumstances enacted the deterioration cycle. Others voyaged around the world, tracking down homes in galleries and confidential assortments or even ground into sexual enhancer powders.”

In spite of having one unblemished Guanche mummy and stays from three dozen others, very little is had some significant awareness of their burial places. “No classicist has at any point found a xaxo in its unique climate,” makes sense of María García. In 2016, a CT output of similar mummy, the best among 40 in exhibition hall assortments, permitted specialists to look into its inside without harming its design.

This isn’t my most memorable excursion to the Canaries looking for replies. Quite a while back, I slid a bluff to investigate collapses the chasm, exploring the legend and counseling specialists to disentangle the starting points of the early Canarians. These islands were viewed as the legendary Lucky Isles, where old Mediterranean sailors had once gone. At the point when Europeans experienced these detached populaces in the Medieval times, that’s what they found, not at all like other Atlantic archipelagos, these islands had been occupied for quite a long time. Annals discussed tall Caucasians, starting different now-disproven hypotheses about their parentage. Leaving the island without indisputable responses, present day innovation has now stopped extremely old mysteries, with the Guanche mummies uncovering their insider facts. One night in June 2016, under close security, the mummy was taken to a close by clinic for a CT check, giving information that exposed a few speculations and revealing the exceptional safeguarding of the Guanche mummy, including the unblemished state of its organs. Radiocarbon dating in 2016 uncovered the mummy to be a tall, sound male, conceivably from the tip top, given the state of his hands, feet, and teeth.