The steppe buffalo, otherwise called the steppe wisent, was an animal groups that once meandered the mammoth steppe. During the last Ice Age, this enormous grassy area extended from present-day Spain eastward to Canada and southward from the Arctic islands to China.

One of the most common large mammals that lived in the vast mammoth steppe was the steppe bison, along with ancient horses, wooly mammoths, and wooly rhinoceroses. Some of the earliest known examples of human art can be found in the steppe bison and human and animal figures depicted in prehistoric paintings in the caves of Altamira and Lascaux.

These superb, long-horned animals went wiped out around quite a while back, during the early time of the Holocene — the ongoing topographical age. They gave rise to the modern bison species, such as the American bison.

As many as 100,000 miners and prospectors from all over the United States traveled to Alaska and the Canadian federal territory of Yukon at the end of the 1890s to participate in extensive gold mining operations during the Klondike Gold Rush.

Around then, numerous excavators coincidentally found antiquated fossils and fragmented stays of ancient warm blooded creatures, however the paleontological worth of such discoveries was typically ignored: The majority of the relics were either thrown away or taken home by workers as keepsakes.

However, in 1976, a family of miners known as the Rumans discovered a highly preserved male steppe bison’s carcass embedded in ice near the city of Fairbanks, Alaska, long after the gold rush had ended.

They named it Blue Darling, regarding Angel the Blue Bull, the legendary sidekick of the American people figure Paul Bunyan, a goliath logger. Fortunately, the family called University of Alaska paleontologist Dale Guthrie as soon as they realized that their find might be unique.

After melting the thick layer of ice and excavating the carcass, Guthrie and his team quickly realized that they had found one of the best-preserved steppe bison specimens ever discovered.

A piece of the animal’s skin was subjected to a radiocarbon analysis, which revealed that it had passed away around 36,000 years ago. The researchers discovered that the bison had most likely been killed by an American lion, a subspecies of the Ice Age lion, the ancient ancestor of the modern African lion, after examining several wounds on its neck and back.

This had likely happened in winter; The dead bison had froze quickly due to the extreme cold, and the vultures were unable to kill it. The carcass was covered in ice and snow for thousands of years, and it sat there, almost intact, waiting for someone to find it.

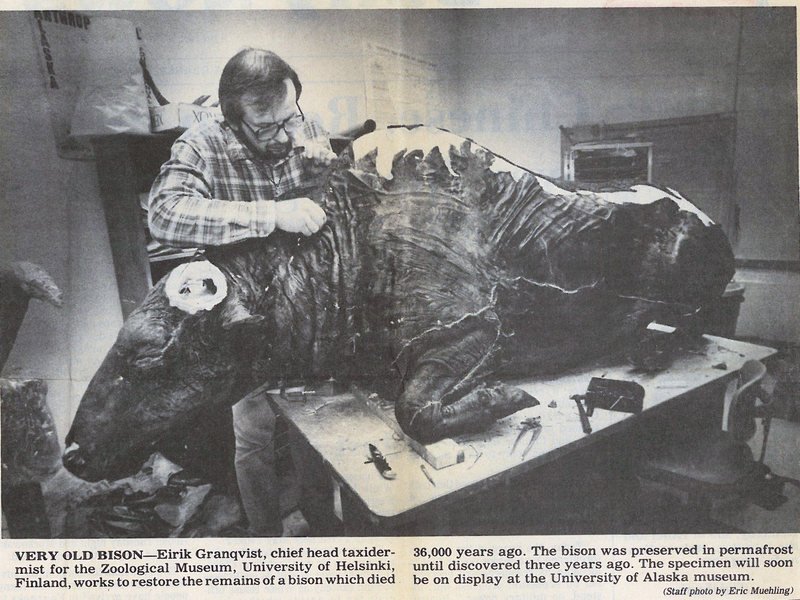

In order for the dead bison to be permanently displayed at the University of Alaska Museum, Guthrie’s research team put in a lot of effort to preserve it in its original state. They even sought the assistance of Eirik Granqvist, the chief taxidermist at the Zoological Museum of the University of Helsinki in Finland. With his expertise in taxidermy, he restored the remains completely and stopped them from decomposing. The team even managed to extract some of the animal’s blood and bone marrow during the procedure.

The specimen was ready for display by the middle of 1984. Guthrie and his team decided to do something unconventional to celebrate their success: They cooked a stew with some of the bison’s neck meat they had removed.

As indicated by Guthrie, the meat was hard and to some degree hard to bite, yet additionally very delectable, looking like standard hamburger. Additionally, the 36,000-year-old meat was clearly quite edible because no one complained of nausea or digestive issues. Blue Darling should be visible shown in the Display of Gold country at the College of The Frozen North Exhibition hall of the North.