An early sign of trepanation could be a hole in a Late Bronze Age human skull found in northern Israel. however, different specialists contend that the opening might have been made for ceremonial purposes after the man’s demise.

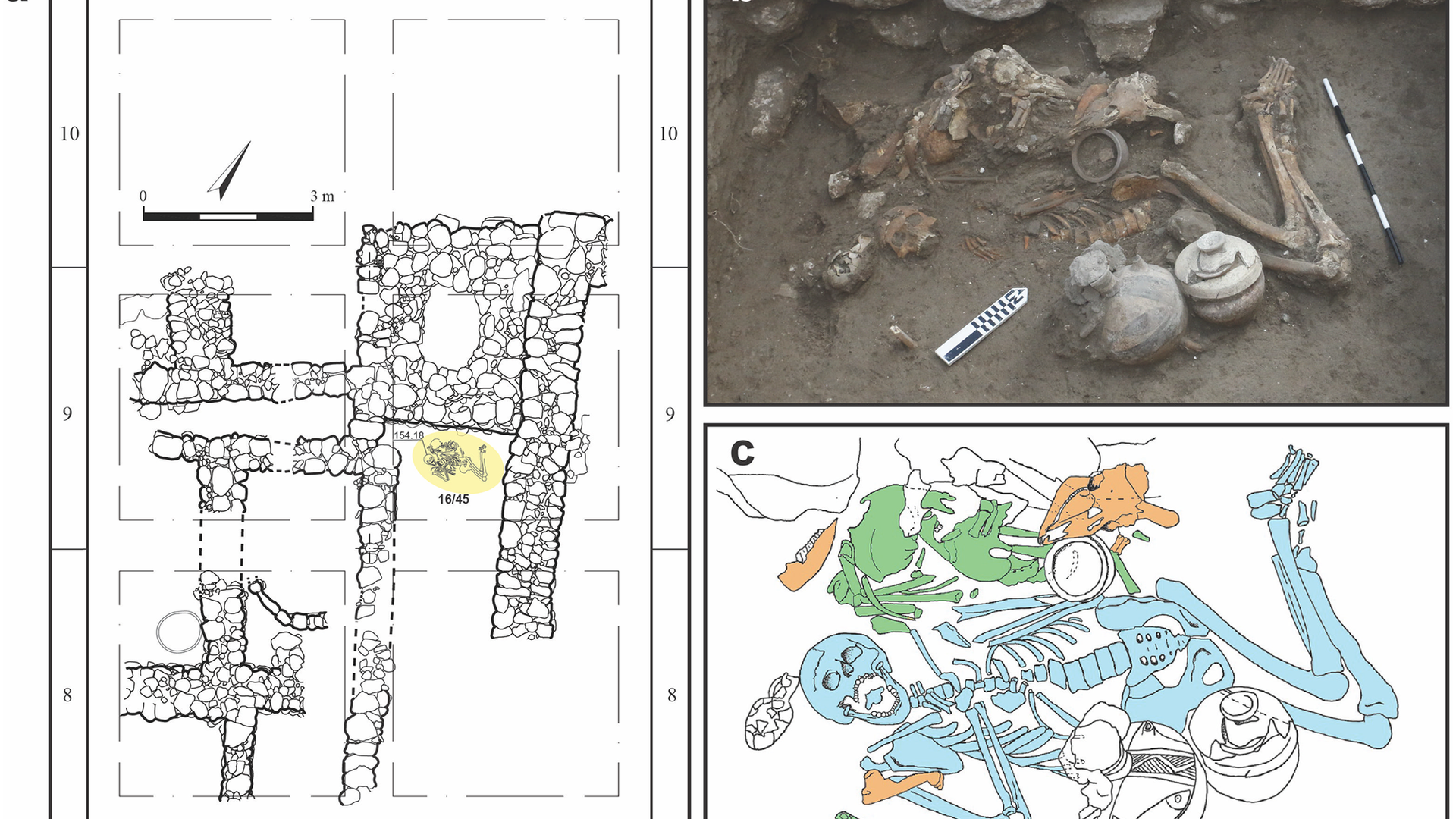

The skeletons of the brothers were found in 2016 at Tel Megiddo, the site of a Canaanite city-state in the Late Bronze Age. The city was the location of several ancient battles and gave its name to Armageddon — the prophesied final battle between God and governments.

The skeletal remaining parts of two Bronze Age siblings covered over quite a while back in what’s currently northern Israel uncover that the kin lived with serious medical issues however approached therapies, including trepanation, another review recommends.

The more seasoned sibling had a piece of bone eliminated from his skull, conceivably trying to treat incapacitating infections, the specialists said. The revelation might be among the earliest proof around here for the act of trepanation (likewise spelled trephination) — making an opening in the skull, ideally without harming the mind — which in old times was believed to be a treatment for different diseases, as per the review, distributed web-based Wednesday (Feb. 22) in the diary PLOS One.

In any case, different specialists dissent, saying the openings probably weren’t intended to be remedial; all things considered, it’s conceivable that the man’s skull was adjusted for ceremonial purposes after his demise.

The skeletons were found in 2016 in a burial place at Tel Megiddo, which was the site of a Canaanite city-state in the Late Bronze Age. An examination of their DNA showed that the men were siblings.

An assessment of the skeletons showed that the two men experienced crippling sicknesses that obliterated a portion of their bones and misshaped others. It’s conceivable that the men were hereditarily inclined toward such illnesses, which might have incorporated a type of sickness, concentrate on first creator Rachel Kalisher, a doctoral understudy in paleontology at Earthy colored College, told Live Science.

Bronze Age bones

Man had HOLE drilled in his head 3,500 years ago, bones show | Daily Mail Online

The examination by Kalisher and her associates recommends that the more youthful sibling was in his late adolescents or mid 20s when he passed on during the Late Bronze Age, between 1550 B.C. furthermore, 1450 B.C., and that the more established sibling was somewhere in the range of 21 and 46 years of age when he passed on a couple of years after the fact.

A 1.2-inch (30-millimeter) square piece of bone was removed from the older brother’s skull. The authors hypothesized that the bone removal, which occurred approximately a week before the man’s death and was a form of treatment for the debilitating conditions he suffered from, occurred as the skull shows no signs of healing.

According to Kalisher, “the totality of evidence is that you have an individual who had suffered from illness for a long period of time, and that perhaps it was a decline.” Therefore, it’s possible that this was an intervention or life-saving procedure.”

She explained, “The hole was made by scoring the skull and carefully levering out pieces from the center, which is different from circular trepanations, which were typically made by drilling or scraping.” She stated, “This example at Megiddo is the earliest in this area of this type of surgery. We have evidence of trepanation in this region that predates the Late Bronze Age.”

Elite burial

Archeologists Stunned After Discovering Possible Purpose of Square Hole in 3,500-Year-Old Skull – 24.02.2023, Sputnik International

According to Kalisher, the fact that both brothers were buried with high-quality food and fine ceramic vessels suggests they were of high social status. Their high status may have been one reason they survived their debilitating conditions for so long, Kalisher said.

Another expert suggested that the square hole indicates the incision was made after his death, possibly for ritualistic reasons, despite the fact that Kalisher and her colleagues stated that the older man’s status might have granted him access to rare surgical procedures like trepanation.

Although Israel Hershkovitz, a Tel Aviv University professor emeritus of anatomy and anthropology, was not involved in the most recent study, he has investigated other ancient trepanations in the region.

In an email to Live Science, he stated, “It is well accepted that cutting the skulls which results in straight-line or square openings were most probably not done for therapeutic purposes.” He added that, despite studies indicating that circular trepanations might have been performed in an effort to treat a condition, that did not appear to be the case here.

According to Hershkovitz, “the shape of the described trephination is square and the walls are vertical.” In the event that this had been finished while the individual was alive, it would have prompted his quick passing.”