Found in boxes inside a church in the Hungarian city of Vác, and analyzed in 2015, the bones of more than 200 years may represent a milestone in science

An old Dominican church was filled with researchers in 1994, in the Hungarian city of Vác. Upon opening mysterious boxes within the sacred site, experts were shocked to find the very well-preserved remains of 265 individuals.

They were not ordinary bones, but surprising mummies. What’s more, they were affected by a disease that, for the dead, used to be quite mysterious.

Mysterious death

The so-called “tuberculosis bacillus” was only discovered by researcher Robert Koch in 1882. The disease is caused by the bacterium Mycobacterium tuberculosis and mainly affects the lungs, causing prolonged coughing, phlegm and fever. However, people in the 18th century did not know its cause.

One third of the individuals thus died of the disease, without knowing the exact reason. It turns out that 90% of the mummies were affected by tuberculosis, even though the patients did not know when they got sick.

And, since the remains were in an excellent state of conservation, this allowed scientists to make a very important discovery for science: It will be possible to better understand the evolution of the disease over the centuries.

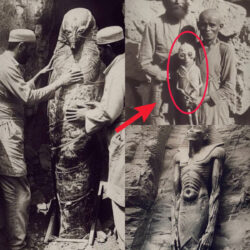

Terézia Hausmann’s mummy, alongside a drawing that represents what she was like before / Credit: Disclosure / University College London / British Journal of Family Medicine

A sick family

Tuberculosis affected an entire 18th century family, which was discovered among the mummies in the boxes.

They were the Hausmanns: There was the corpse of the older sister, Terézia Hausmann, who died at the age of 28, on December 27, 1797; and there was also the mother’s mummy, whose name was unknown; and the younger sister, Barbara Hausmann, whom Terézia took care of.

The three, however, died of tuberculosis. Terézia 4 years later, after taking care and watching her mother and sister die.

What was very useful, however, is that the deaths occurred at a time prior to the use of antibiotics, which means that the bacteria had not yet undergone mutations generated by these drugs.

As reported by Revista Exame, anthropologist Ildikó Szikossy, from the Natural History Museum of Hungary, considered the discovery to be capable of bringing “new paths of medical research, which can be used by modern medicine”.

In an interview, the specialist also said that at that time there were several strains of the disease, which coexisted at the same time. When analyzing the DNA of the mummies, they found ramifications that originated in the Roman Empire. Only Terézia Hausmann’s mummy, for example, had two different types of tuberculosis bacteria.

The discovery was published in the scientific journal Nature Communications. “It was fascinating to see the similarities between the sequences of the tuberculosis genome that we recovered and the genome of a recent strain in Germany,” commented in a statement, Mark Pallen, professor of Microbial Genomics at Warwick Medical School, UK.

Still according to Pallen, the study may help in tracking the evolution and spread of microbes. It also “revealed that some [bacterial] strains have been circulating in Europe for more than two centuries,” said the expert.

Terézia Hausmann’s mummy. Natural History Museum of Hungary

Mummification

For the convenience of the researchers, the corpses had been deposited in the Hungarian church between the years 1730 and 1838, so that it allowed their conservation. It all happened because, in the 1780s, King Joseph II prohibited burials in religious crypts, where the dead were placed on top of each other, without separation, which was increasing contamination in the region.

However, residents of Vác did not respect the monarch’s ban. By cultural tradition, they went to the Hungarian church and placed several bodies of important people there. Until, in 1838, the place was finally closed.

The small cathedral, then, fell by the wayside. However, the temperature of the cold place, which varies between 8 and 11 degrees, and its high humidity of 90%, allowed for a natural mummification process.

It may also have helped the wood chips placed in the bottom of the coffins, which absorbed body fluids, and the natural antimicrobial agents of the pine resin in the coffins. The internal organs were thus almost intact, allowing the tracking of tuberculosis bacteria.

The mummies were transferred to the Natural History Museum in Hungary. According to data from the World Health Organization, the bacterial disease that killed them today still kills 4,500 people every day in the world, according to data from 2019.

The answer to new treatments against tuberculosis may lie in paleomicrobiology, the fascinating study of how microbes acted in the past.