In 1909, a New York financial specialist named Samuel Brown made a trip to Egypt to buy a couple of old mummies for the Albany Establishment of History and Workmanship, where he filled in as a board part. Brown and ages of ensuing specialists accepted that he brought back a female mummy dating from the 21st Tradition and a male one from the Ptolemaic time frame.

Yet, when Emory College Egyptologist Peter Lacovara visited the foundation in the mid 2000s, he felt that the female mummy wasn’t in that frame of mind in which she was initially covered. Perhaps it was anything but a mummy of a lady by any stretch of the imagination.

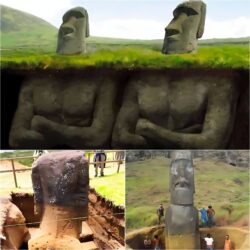

Top or more: Opened up and wrapped mummy of Ankhefenmut from the 21st Line (1069-945 B.C.) found in Bab el-Gasus, Egypt. Antiquarians initially believed that Ankhefenmut was aw oman. Picture credit: Albany Organization of History and Workmanship, endowment of Samuel Brown, 1909

Lacovara realize that different galleries have made mistakes in “Sexing mummies,” so he proposed to filter the remaining parts on GE processed tomography (CT) and X-beam hardware at the Albany Clinical Center.

The tests affirmed his hunch. The 3,000-year-old mummy of a “lady” had a male pelvis and a man’s thicker and rakish bones. The group likewise saw that the upper right half of the mummy’s body “was determinedly more solid.”

This reality, joined with markings on the casket, drove the specialists to reason that the mummy was Ankhefenmut, a minister and stone worker at the Sanctuary of Mut close to Luxor, who lived between the years 1069 and 945 BCE.

Egyptologist Peter Lacovara (focus) concentrated on Ankhefenmut on a CT scanner made by GE. Picture credit: GE Medical care

Such are the wonders of current clinical innovation that the sweeps yielded different fortunes. The specialists observed that the mummy’s bones were “all around mineralized, strong and uniform,” demonstrating that Ankhefenmut’s eating regimen “contained satisfactory protein and calcium.” What’s more “his dentition was excellent, without any holes or loss of teeth.” He was around 50 when he kicked the bucket.

In 2013 the Albany Establishment welcomed Lacovara to arrange a show that revised the tale of its mummies. The show, “GE Presents: The Secret of the Albany Mummies,” opened a year after the fact.

This wasn’t the initial time GE clinical innovation assisted antiquarians with investigating the past. In 2011, anthropologists from the Milwaukee Public Gallery checked mummies from Peru and Egypt, including the top of an Egyptian man named Djedhor.

Djedhor was first checked in 1986. In any case, in 2006 a fresher innovation uncovered an opening in his skull, which drove anthropologists to presume that he had gone through a crude type of cerebrum medical procedure.

“We’ve been doing this for a very long time with GE,” said Carter Lupton, the Milwaukee exhibition hall’s head of humanities. ” Each opportunity we’ve emerged, it’s an alternate age of innovation, better imaging, better data, better ways, and it’s quicker as well.”

GE has been helping students of history check and recognize mummies starting around 1939. in those days, GE clinical scanners delivered X-beam pictures of mummies for the New York World’s Fair (above). Picture civility of the New York Public Library.

CT scanners produce nitty gritty pictures of the human body. The most recent imaging frameworks like GE’s Upheaval CT convey dazzling pictures of organs, bones, veins and other body parts. Picture credit: GE Medical services